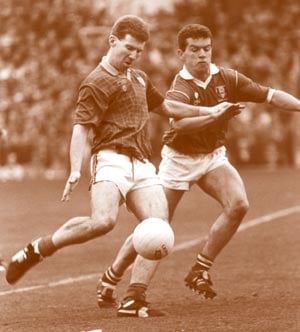

O'Malley, Bob

December 06, 1991

Bob O'Malley

Bob O'Malley

Looking forward to many more years in the top flight

by Jimmy Geoghegan

"He came in and laid down the law. He said that we either put the head down now or we forget about it. He said that we would win nothing unless we start to work really hard. It was up to us." Bob O'Malley remembers the moment with intense clarity. The moment that Sean Boylan called the Meath team together for a meeting. A crisis meeting that was designed to clear the air and get the record straight. It was the spring of 1987. "We had just been hammered by Galway in the quarter final of the league. It was a surprise result at the time, because some people had been tipping us for the All-Ireland. I think that we were believing them too much, because I suppose things got a big lax and fellows were not turning up for training or anything."

Looking back on it now, Bobby O'Malley remembers the Meath manager's warning as one of those momentous turning points in the journey of a group of men in their quest for a cherished objective. Like a sharp bend in the course of a great river. Sean Boylan had been at the helm of the Meath ship for five years, steering it through some trouble waters, but on the way collecting some trophies. Small triumphs such as an O'Byrne Cup or the Centenary Cup, little indications that things were coming together. Signs of future prosperity.

But then everything seemed to come to a halt, with the humiliation dished out by Galway. And there was a price for the players to pay. "We had all decided to give it a go and a week after the meeting we were in Bettystown running up and down the beach. The training was unbelievable. When Sean Boylan took over in 1982, he took the training up a gear and people thought that this was the limit. But he brought it up another gear in '87 and it was the making of the team that year.

Less than seven months later Boylan, O'Malley, O'Rourke, Lyons and the rest were being hailed as heroes, as they travelled down home with the Sam Maguire for the first time in twenty long years. Journey's end had been reached. The beginning of that journey was for Bobby O'Malley back in the autumn of 1983, when he was picked to play for the Meath seniors. It was a natural progression, since he had already moved up through the ranks. He had played under 14, under 16 and he was part of the Meath minor team since he was 15 years of age.

By the fall of '83, Boylan had been in charge of the Meath team for over a year and after the long years of despair through the seventies, it had become fashionable once again to play in the green and gold. Suddenly everybody wanted a role and when the young O'Malley, who was only eighteen, was given his chance, he did not hesitate to take it. After a few challenge games, O'Malley made his first competitive outing against Down in the League in 1984.

But it wasn't quite like a new piece of the jigsaw that had nicely fitted into place. His early appearances were at right half forward, not in his now customary right full back berth. But a finger inquiry to Mick Lyons in the 1984 championship caused him to be pushed back into defence and his niche on the team was finally found.

The big breakthrough for Meath, as far as O'Malley is concerned, was beating Dublin in the Leinster Final in 1986 and getting to the All-Ireland semi final. This was the first big progressive leap. "I suppose that we could and should have beaten Kerry in the semi final and the mix up in our goalmouth that allowed Ger Power to score their goal certainly didn't help. I always consider '86 as part of our learning process towards winning the All-Ireland and to our credit I think that we did learn from the defeat."

The following year it all came right for the Royal County, as a decisive first half Colm O'Rourke goal helped them to defeat Cork. And winning an All-Ireland - the dream of every inter county player had finally become a reality. Reflecting on that day now, O'Malley sees it through a new perspective. "I always think that when you are involved at the time you don't appreciate it. I think that as you get older and look back on it, then you realise the importance of the day and just how much a great occasion it was."

For O'Malley, an intense and deeply emotional man, the victory in 1987 was a very emotional affair, the fulfilment of a genuine dream. But the homecoming afterwards, for a player who is particularly aware of the rare relationship that exists between team and the people, was simply overwhelming. "I will never forget, as long as I live, just seeing the sea of faces as we came into places like Summerhill, Trim and Navan. Everybody seemed to be cheering and waving flags. The depth of feeling, particularly in Summerhill, because Mick Lyons was captain, was just incredible. I cried above in the stand that night." The celebration seemed to go on for months.

"I didn't work for a week afterwards but the win was fabulous for the county and the people, in their everyday lives, their business, their family lives. It gave the whole county a lift up."

But personally for O'Malley, 1988 was a more satisfying victory, partly because it had been achieved after a drawn game, when it all looked lost for Meath. "It was very close in the first game, because we were five points down with only ten minutes to go, but we clawed our way back and won it in the replay. But I always feel that you have to win a second All-Ireland to show that you deserved the first." But there was other reasons. Stung by the criticism voiced in some parts of the national media that Meath used over robust tactics, O'Malley and his colleagues were determined that such critics should not be given the chance to call Meath one year wonders.

"We never denied playing physical but to accuse us of playing dirty, really got up our backs. There was great resentment among the players towards some sections of the media and we have to thank them for the part they played in the '88 win, because the more they wrote about us, the more we were determined to succeed."

For O'Malley, his colleagues on the Meath team are not only team mates, who meet up occasionally to prepare or play in a game. They are members of a cohesive, family-like unit. "The family bond among the players is very tight, very strong. The team socialises together most of the year. We play golf together. We are particularly close as a unit and we all have made some great friends out of it. Like all families, if someone talks about one member, we will defend. united we stand."

But like any group of people who have travelled together on a hazardous journey, there have been some truly harrowing moments. One of those was when Meath were defeated by Down in the All-Ireland last September. It was a sorrowful end to a tragic few weeks, for Bobby O'Malley in particular. In the opening minutes of the Leinster Final, O'Malley broke his leg. He was told by the surgeon that he would be at least six weeks in plaster and as Meath progressed to the All-Ireland Final, the terrible thought of missing out intensified. "I was not prepared to accept that I would miss the game. I did things that I should not have done. I got the plaster off very early and I was up on a bike soon after that. I was simply desperate to play. But I had to push myself, just so I could always say that I tried." All the effort was to no avail. The big match day approached and O'Malley had to suffer the sight of watching his colleagues, friends run onto Croke Park to the roar of the crowd.

"As you move on in life you see that playing in the All-Ireland Final is what it is all about. I know good players who will never get near an All-Ireland. So, when you get to a final, you like to be able to play in them. It was terrible hard to stand back in the dressing room and watch the lads go out. It nearly killed me," he recalls. But O'Malley's feeling of loss was compounded a little over an hour later, when the team returned a Downtrodden and vanquished group of men.

"I could never forget the dressing room afterwards. It was far worse than the previous year. I saw men cry that I didn't think would ever cry. It was very rough because we had worked so hard to get that far. We had beaten Dublin and we had played six games before we even got into the Leinster semi final. I felt particularly sorry for the older players."

As Bobby O'Malley's memory remains haunted by that black day in his career, he has many other brighter moments to recall. One of the biggest was his role in the Irish Compromise Rules team that travelled to Australia in 1990. It was a memorable moment for him, made even more so by the fact that he was made captain. One of his outstanding memories of the entire tour, was giving his first talk to the team in the hotel soon after their arrival. "It was a very humbling experience for me, because I looked around and saw some of the most famous faces in gaelic football. People like Jack O'Shea and Eoin Liston, who I watched playing when I was growing up. I asked for their support in performing the task of captain and I got it."

For O'Malley, the Compromise Rules is not just a great experiment, it is the way of the future. "I firmly belief in the Australian concept. It is the lifeline of the GAA in the years ahead. Compromise Rules game is fairly close to what I would like to see for gaelic football in the near future. Football that is much faster, where the players are fitter. The type of games that more people will come and see."

For O'Malley, commercialism has an important place to play in his vision of the game. "We have as good a game as any in the world, but if we market the game better we could be very pleased with the kind of feedback we get. But the governing body must be more open-minded about rules and allow more commercial involvement, and the players should be paid for their efforts, with every county board acting in the same way as a Board of Directors does in soccer."

These days O'Malley is enjoying a new lease of life as a publican in Navan, following stints as a bank employee and a sales representative. It is a new challenge for him and one he faces with relish. Yet while chancing his career over the past number of years, he as remained a constant member of his team - St. Colmcilles. Since he was seven years of age, O'Malley has lined out in the club colours, moving up through the underage teams, helping them to win the Junior Championship and later still, the Intermediate in 1988. Fearful of gaining the name of a 'medal hunter', O'Malley is anxious to dispel rumours that he is about to join one of the big clubs in the Navan-Trim area. "The club is the cornerstone of gaelic football and I don't see players chopping and chancing unless they have good reason. No, I'm staying with St. Colmcilles."

At 26, Bobby O'Malley looks forward to many more years at the top level of gaelic football. But he knows the sport has been good to him. He has travelled many parts of the world playing it, gaining experience both in the game and in life. "Football is a great teacher. It shows you, for instance, the value of hard work. I don't like training but in a team game it's vital. Football, like life, is a rocky road and when you are down it is hard to be optimistic. But you have to keep at it and eventually it will come right."

Advice from a man who knows.

Taken from Hogan Stand magazine

6th December 1991

Most Read Stories